In Ike Snopes and Jack Houston, William Faulkner gives us pastoral heroes twinned in tragedy, their harmonized losses amplifying The Hamlet’s elegiac theme of a natural world sacrificed to commercial corruption. Each man achieves a profound spiritual “animal husbandry”; Ike marries a cow, while Houston marries as a stallion. And both characters run fatally afoul of the Snopes clan’s own distorted animal husbandry, a mercantilism in which the transcendent natural world is not beloved, but merely bought and “beefed.”

As often happens in The Hamlet, it is the decent bystander Ratliff who sets the novel’s marital theme into a moral framework. Chapter One of Book Three, “A Long, Hot Summer,” opens with Ratliff angrily pondering the recent forced wedding between the pregnant Eula Varner and the rapacious Flem Snopes:

What [Ratliff] felt was outrage at the waste, the useless squandering; at a situation intrinsically and inherently wrong by any economy, like building a log dead-fall and baiting it with a freshened heifer to catch a rat… (page 176)

Eula’s marriage to Flem is perverse, unnatural, fiduciary. Flem Snopes, ceaselessly acquisitive and coldly asexual, is the man least able to husband Eula’s animal fecundity.

Not coincidentally, Ratliff immediately goes from musing on Eula as “freshened heifer” to learning of two additional, interconnected bovine dilemmas. On Varner’s storefront porch, Ratliff hears talk of a legal imbroglio involving widower farmer Jack Houston impounding Mink Snopes’s bull for pasturing fees. Then, an invitation is leeringly extended to Ratliff from the men and boys on the Varner porch to observe some furtive, unnamed farcical burlesque, which we learn later is the sexual union of the childlike Ike Snopes and a cow.

But rather than subjecting us to this peep show right away, Faulkner hurries us on to Chapter Two, in which we pass with Ike from local gossip and sordid mundanity into the realm of the mythic natural world. Here Ike Snopes, with no language other than Faulkner’s soaring lyrical rendering of his sensory experience, embarks on a classical courtship of his beloved. His pursuit elevates him from shambling, drooling, moaning “stock-diddl[er]” (222)into successful pastoral lover.

Ike pursues, cajoles, adores the cow, who is traditionally reticent, elusive, and beautiful. The pursuit turns conventionally heroic as Ike rescues the cow from the barn fire, shouldering her out of the ditch and towards the creek, where she finally rewards his ardor by allowing him to touch her:

She does not even stop drinking; his hand has lain on her flank for a second or two before she lifts her dripping muzzle and looks back at him, once more maiden meditant, shame-free. (page 193)

With the cow’s acquiescence, Ike’s pursuit becomes holy union. Not even Houston, the cow’s “legal” owner, can dissuade Ike. He skillfully elopes with the cow into the woods, where they eat together and he festoons her with flower petals, recalling Keats’s Ode on a Grecian Urn: To what green altar, O mysterious priest/Lead’st thou that heifer lowing to the skies,/And all her silken flanks with garlands drest?

This chapter concludes with a symbolic wedding night, the couple “nestling back in the nest-form of sleep, the mammalian attar. They lie down together.” (206) Ike has achieved literal animal husbandry. He both shepherds the animal, and is her mate.

Houston, the cow’s owner, interrupts Ike’s extended reverie twice; in fact, Ike and Houston encounter each other only twice in the novel. Both times, they meet in a vivid natural world of animals and animal imagery.

Houston has his own animal cohorts. He is repeatedly described as a widower with no family, but his uncannily wise dog, who mourns and attempts to avenge him after his murder, is omnipresent. In Houston’s first encounter with Ike, the dog drives Ike away not by barking but “shouting.”(185) The dog behaves as a sort of interlocutor, Houston’s animal intermediary. In Ike and Houston’s second encounter, in the creekbed, Houston approaches on a galloping horse he controls solely with his voice, bareback and “without even a hackamore,”(194) in an image of preternatural horsemanship. Where Ike is able to enter spiritual union with the cow, Houston seems to employ a kind of animist horse-and-dog magic.

Houston’s animism extends to his role in animal husbandry, a term with a double meaning for him as for Ike. But whereas Ike is an animal’s husband, Houston is the animal—-a headstrong horse-man tamed into good husband-ship by a plain and patient girl in “dove-colored clothing.”(227)

Chapter Two of Book Three says of Houston, at fourteen years of age, that he is “not wild, he was merely unbitted yet.”(228) Faulkner goes on to characterize Houston, in his return to Frenchman’s Bend and Lucy, as:

…the beast, prime solitary and sufficient out of the wild fields, drawn to the trap and knowing it to be a trap, not comprehending why it was doomed but knowing it was, and not afraid now—and not quite wild. (237)

A contrast to Ike and the cow, in Houston’s marriage courtship it is the female who pursues. Even gender-reversed, theirs is nevertheless a classical pastoral romance. Lucy, like Ike, pursues her beloved ardently. She cajoles, offering him the classic horse-bait of apples from her school lunchbox, and attempts to tame him through education, which he resists. A schoolyard wag even observes that Lucy “was forcing Jack Houston to make the rise to the second grade” (page 231), mirroring Ike’s shouldering the cow up the rise from the ditch during the barn fire. Ike is rewarded for his pushing with a torrent of cow manure; Lucy is rewarded for hers with thirteen years of resistance before Houston finally succumbs to her.

Interestingly, Houston’s rootless, “bitless” masculinity, his emergence in Yoknapatawpha County from the wild newness of Texas, even his surname, evoke the dangerous Texan horses that Flem Snopes and Buck Hipps inflict on Frenchmen’s bend a few chapters later. It’s as though bovines are Faulknerian shorthand for everything domestically female and fecund, while equines suggest masculine violence and chaos, as we see in Lucy’s death:

Then the stallion killed her. She was hunting a missing hen-nest in the stable. The negro man had warned her: “He’s a horse, missy. But he’s a man horse. You keep out of there.” But she was not afraid. It was as if she had recognized that transubstantiation, that duality, and thought even if she did not say it: Nonsense. I’ve married him now. (239)

This stallion-man transubstantiation is a mysterious and ambiguous one. Perhaps her dismissal of the stablehand’s warning suggests some tragic hubris on Lucy Houston’s part; she believes her taming of her stallion husband has inured her to any stallion’s violence. Perhaps Faulkner is suggesting that no husband is a good idea; after all, The Hamlet’s array of male spouses contains a wife-beater, a murderer, a despot, and a frog. Or perhaps Faulkner is suggesting that any romantic pursuit involves a degree of hubris, as well as risk of unbearable loss.

Houston’s mourning for his wife and instinctive understanding of pastoral love inform his decision to give Ike the cow. Although money changes hands, it is an unnamed and uncounted sum, more a ritual gesture than a commercial endeavor. Among the male characters of The Hamlet, Houston and Ike are the least mercenary; and where Houston has little interest in money, Ike has less than none, as Mrs. Littlejohn points out. “What else could he do with [the money]?’ she said. ‘What else did he ever want?’”(216)

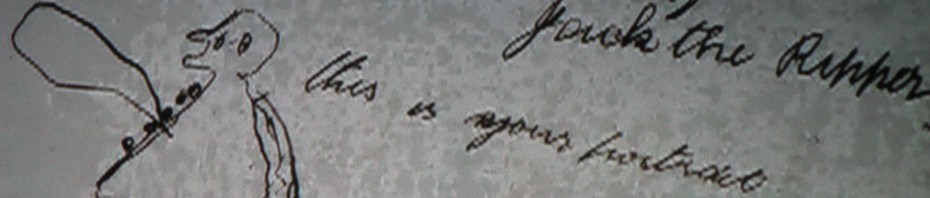

But Ike loses his sacred cow to his cousin Snopeses, who conspire to purchase and slaughter “the partner of his sin” and feed her to him, supposing that this may cause him to “chase nothing but human women.” (223) As I.O. Snopes dickers with his cousin Eck over their relative financial contributions towards the beloved cow’s “beefing,” he refers to the act as “sacrifice to the name [we] bear.” (225) I.O. worries specifically that further public perusal of Ike’s love life may undermine the Snopes clan’s many financial and political dealings. Faulkner spares us the details of the beefing, but we do catch a glimpse of Ike some time afterwards, despondently clutching a wooden cow doll as emblem of his loss.

Like Ike’s cow, Houston can be seen as a sacrificial animal, Lucy’s stallion husband murdered by Mink Snopes over a three-dollar pasturing fee. In a final Snopesian insult to his and Ike’s shared pastoralism, Mink Snopes attempts to rob Houston’s corpse. The money on his person, which Mink does not recover, is Ike’s useless and dead money, the beloved cow’s bride price.

Works Cited

Faulkner, William. The Hamlet. New York: Vintage Books, 1991.

Keats, John. “Ode on a Grecian Urn.” Class handout